The Death of the Timer: Why Your Toaster Has Been Lying to You

Update on Dec. 15, 2025, 8:55 a.m.

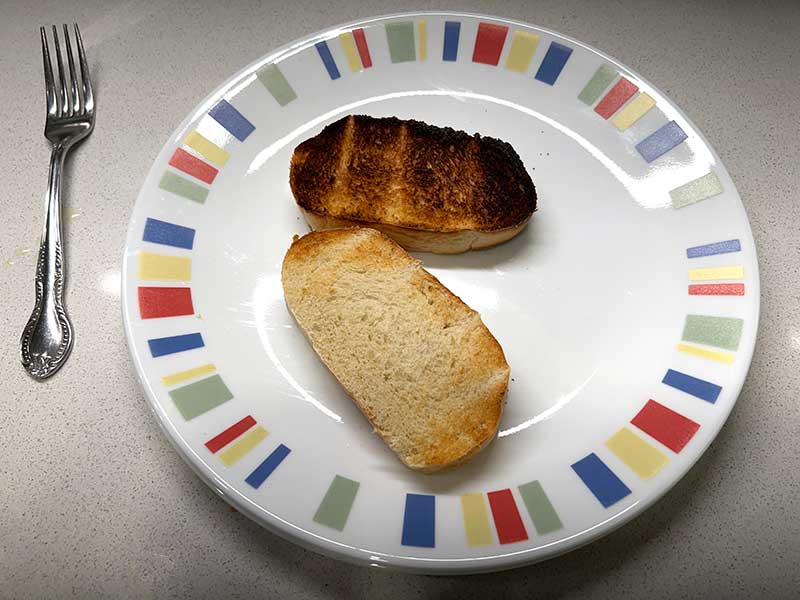

In the pantheon of kitchen appliances, the toaster is often dismissed as a simpleton. It is a box of hot wires, a spring, and a timer. You put bread in, you wait, and you hope. But anyone who has engaged in the morning ritual of breakfast knows the inherent betrayal of this machine. The “3” setting that produced a perfect golden crisp on Tuesday delivers a charred, smoking ruin on Wednesday. Why? Because the dial on your toaster is not a promise of results; it is merely a promise of time. And in the chaotic thermodynamics of browning bread, time is a terrible proxy for doneness.

The Tineco TOASTY ONE arrives not merely as a luxury appliance, but as an engineering critique of this century-old failure. At $339, it is easy to mock as a symbol of tech-excess. However, to look past its ivory-white porcelain finish and LCD screen is to miss a fundamental shift in how we approach cooking energy. It represents the transition from blind mechanism to watchful intelligence—a shift from open-loop to closed-loop control.

The Tyranny of the Open Loop

To understand the Tineco, one must first understand the flaw it seeks to correct. Traditional toasters operate on an open-loop system. The user provides an input (the dial setting), and the machine executes a pre-set command (heat for 120 seconds) without any knowledge of the output. It is blind.

The core technology of this blind system is usually a bimetallic strip or a simple capacitor timer. The bimetallic strip bends as it heats up, eventually tripping the switch to pop the toast. The problem is that the strip reacts to the ambient heat of the toaster, not the state of the bread. If the toaster is already hot from a previous cycle, the strip bends faster, popping the bread prematurely. If the bread is frozen, the strip doesn’t know to extend the time. The machine is reacting to itself, oblivious to the food it is tasked with transforming. This disconnect is the source of all burnt toast.

Enter the Closed Loop: Digitizing the Maillard Reaction

The TOASTY ONE replaces this blindness with sensors. It employs IntelliHeat technology, which is marketing-speak for a closed-loop feedback system. Inside the slots, sensors monitor the surface of the bread hundreds of times per second. They are not looking at the clock; they are looking at the color and moisture content of the slice.

This is a profound difference. When you drag the slider on the 4-inch LCD touchscreen to a specific shade of brown, you are not setting a timer. You are defining a target state. The microprocessor then throttles the 1200-watt heating elements in real-time to guide the bread toward that state.

The goal is to navigate the Maillard reaction, the complex chemical dance between amino acids and reducing sugars that occurs between 280°F and 330°F. This reaction creates the hundreds of flavor compounds we recognize as “toast.” It is a volatile process. A few degrees too cool, and you just have dry, warm bread (dehydration without browning). A few degrees too hot, and you hit pyrolysis (burning).

By monitoring the bread’s surface temperature and color, the Tineco system attempts to hold the bread in that “GoldenCrispy” window—optimizing the browning of the exterior while preserving the moisture of the interior crumb. It stops not when a clock runs out, but when the Maillard reaction has reached the precise point you requested.

The Paradox of Perfection: The “Bagel Problem”

However, the pursuit of algorithmic perfection often stumbles on the messy reality of human habits. In designing a machine that is obsessed with achieving a perfect, uniform result on both sides of a slice, Tineco’s engineers seemingly forgot that not all toast is symmetrical.

The device lacks a dedicated Bagel Mode. A bagel, by definition, requires asymmetric heating: high heat on the cut side to caramelize the starch, and gentle warming on the crust side to keep it chewy. A cheap $20 toaster achieves this by simply turning off the outer heating elements. The Tineco, with its sophisticated sensors and pursuit of “evenness,” struggles to comprehend that sometimes, unevenness is the goal. It toasts the bagel on both sides, treating it like a thick slice of white bread.

This is the classic trap of over-engineering: optimizing for a specific metric (uniformity) at the expense of versatility. The closed-loop system is so effective at its primary directive that it lacks the flexibility to break its own rules.

The Geometry of Sensors

Another limitation of this sensor-driven approach is revealed by simple geometry. The sensors are fixed in place. If you insert a slice of bread that is significantly curved—like the heel of a rustic loaf—parts of the surface will be closer to the heating element, while other parts recede.

In a dumb toaster, the radiant heat would blast the whole area regardless. But in the Tineco, the sensor might read the protruding part of the bread as “done” because it browns faster, triggering an early shut-off. This leaves the recessed areas under-toasted. The machine is technically accurate—the part it saw was indeed ready—but practically failing. It highlights the difficulty of applying digital logic to the analog irregularities of artisanal baking.

Conclusion: The Cybernetic Breakfast

The Tineco TOASTY ONE is more than a kitchen gadget; it is a case study in the benefits and limits of computational control. For standard sliced bread, it offers a consistency that no mechanical timer can match. It frees the user from the guesswork of the dial, delivering a repeatable result regardless of whether the bread starts frozen or fresh.

It validates the idea that cooking is physics, and physics can be solved. Yet, its inability to handle the simple asymmetry of a bagel serves as a reminder that cooking is also culture, and culture often defies strict logic. The Tineco is a brilliant, specialized tool for the purist of the slice, a machine that finally tells the truth about doneness, even if it doesn’t quite understand the poetry of a bagel.